It’s been so cool to see the energy building around FilmStack and the NonDē film movement. Feels like every day there’s more momentum, and it’s exciting to be part of it. I’m guessing most of you already have a sense of what it’s about since there have been a bunch of posts diving into different pieces of it. But if you're new or just want a clearer picture, check out

’s NonDe Manifesto, it lays out the foundation of it.A lot of the conversation around NonDē has focused on the business side of things, which very well may be the central point of it all. It’s about creating cinema that doesn’t rely on the traditional systems or platforms for any part of the process. There have been some great posts about the importance and power of building your own audience , which, for a lot of us, is the whole reason we started a Substack in the first place. The collaboration and sharing of knowledge is also key to the movement. It’s all been incredibly helpful and inspiring.

The part about this movement that resonates with me most is the artist forward thinking behind of all it. As Ted Hope state’s in his NonDē Principles:

The artist and the art come first. Some may be the fascinated by the business, but it begins with the art and those that create it.

Sure, we need to create systems that sustain the artists, but we also need to put the focus on creating cinema that reaches for more than it currently does. Cinema that has personal vision, a unique voice or perspective, cinema that has something to say, cinema as art.

Some of you might be rolling your eyes right now, but bear with me for a second. I get that the word art, especially arthouse when it comes to cinema, may have negative connotations. For some, it brings to mind films that feel pretentious or boring. But that’s not exactly what I’m talking about. Art doesn’t have to be that.

When I say art, I mean cinema that reaches for more and what more means can look completely different depending on the filmmaker. I am being intentionally vague here by using the word more, because what that more is will vary greatly depending on the project. It's about intention, ambition, and pushing past the expected, whatever form that takes.

Ted Hope’s NonDē manifesto also touches upon this in number 5:

NonDē supports and encourages boldly authored work willing to explore new perspectives, story forms, aesthetic approaches, and distinct expression of all types.

Of all types is key. It’s not a limited elitist perspective. All types of film can reach for more.

So what do I mean by more?

Cinema that reaches for more trusts its audience. They often embrace ambiguity. These films don’t over-explain, they leave space for the viewer to interpret, to decide for themselves. Sometimes that shows up in the ending, sometimes in the details along the way. A great example of this kind of filmmaking is The Fits (2015), when the dancers in the film begin experiencing unexplained seizure-like "fits," the film avoids offering any explanation. Instead, the fits serve as a metaphor for the pressures of adolescence and the influence of group dynamics. The film embraces ambiguity, trusting the audience to find meaning without explicit answers.

Another thing about cinema that reaches for more: it uses everything at its disposal to serve the film’s message. It’s not just about camera angles or lens choices, it’s also sound, production design, color, pacing, tone, performance. All of it matters. And the best films take the time to make sure all those pieces are working together to say something meaningful. A terrific example of this is The Zone of Interest and the use of sound. Throughout the film you can hear the horrifying sounds coming from the concentration camp, even if you cannot see it. This enforces the theme of the banality of evil, as we hear it existing just beyond the families walls while they are doing their normal everyday activities and the contrast of sound and image is the point.

Cinema that reaches for more also pushes the technical side of filmmaking, trying out new techniques or fresh ways of doing things. Take Requiem for a Dream, when it came out its rapid-fire editing and unconventional camera angles really added to the film’s intensity and pushed the boundaries of filmmaking itself further.

It’s also about tackling topics that society usually avoids or hides, challenging the status quo. Anora or any of Sean Baker’s work is a great example, as it explores and humanizes sex workers, shining a light on their lives in a way that’s honest and empathetic. Focusing on this across his work, he aims to de-stigmatize and bring humanity to a group that’s too often misunderstood.

The more is always done in service to the work as a whole.

Ted Hope (yes I know I’m mentioning him again but you know, the man knows what he is talking about and his films prove it) calls this more - ambitiously authored cinema.

Ambitious film will do more than just give the audience what it wants. To simply provide is all but to pander. Ambitious film takes us into new ground where we question our place and ourselves.

I love using this term because using the word ambitious leaves room for how varied the films can be. It’s open to all types of work.

To some perhaps ambitious is too open, what exactly is ambitiously authored cinema?

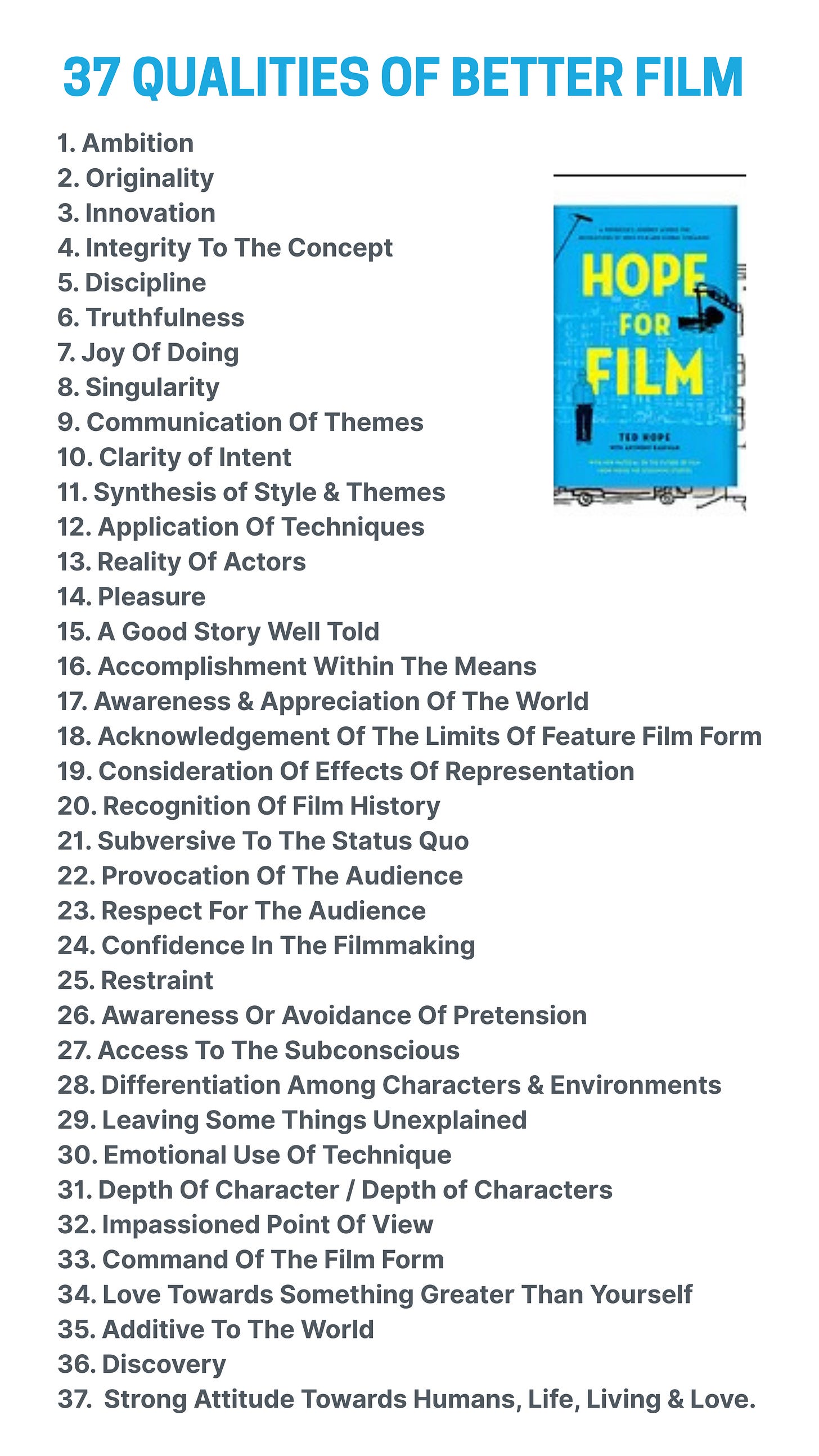

Well, Ted Hope has put together a great list of the key qualities that define this kind of filmmaking. I’ll share them below (in the spirit of NonDē I took the liberty of creating an easy to see visual representation of the qualities Ted listed that make better film, hope that’s okay Ted?). These are all him, not me.

You can check out his full posts, where he expands upon these qualities.

Originally it was 32 Qualities, which you can find here.

Then he expanded by 5 more, making it 37 total. Which you can find here.

This is the kind of cinema we desperately need right now.

Does NonDē need to be defined more by this as well? Is it enough for a film to be made non-dependent of the system or does it need to adhere by these aesthetics values as well?

And how have we gotten to this point with cinema? Why are more filmmakers not reaching for more?

’s on his Rough Cuts wrote a great post about closed-loop cinema and how so many films today are just repeats of past films. In it he states:However good they are - and some truly are great - these movies are strict subsets of earlier films. Their ambitions feel constrained, their identities small. This closed-loop cinema feels oddly hermetic: cinema as Narcissus, obsessed with its own reflection.

This post made me wonder, are filmmakers aware that they are doing this? Do they know that they are writing scenes based on earlier scenes they’ve seen in old films? Do filmmakers know their films are not as original as they could be?

The bigger question this brings up for me is this - is it the filmmaker fault?

I would say “no”, it is the system’s fault.

I won’t go into how the Hollywood, the Independent Film system, or streamers have effected this, as many have already written posts on this much better than I could.

But I will discuss my take, which is that the educational institutions are largely to blame. A lot of American film schools are trapped in the past or too focused on the nuts and bolts of filmmaking, not the theory or art of it. A friend of mine used to teach at one of the top graduate film programs, and most of the professors there were old-school filmmakers stuck on outdated methods and strict three-act structures. There was little to no focus on exploring new ideas or techniques. This professor friend even launched a new class there that quickly became the most popular graduate course. Students loved it, and the thesis films from those years really stood out, with some even snagging Student Oscar nominations. What a great opportunity for the school to rethink some of its curriculum. Instead what did they do? They canceled the class and didn’t invite the professor back. And why? Because those fresh approaches and the push to get students thinking differently clashed with the old professors’ methods. They couldn’t keep up. The new ideas just didn’t “fit” within the program, so it had to go.

Don’t get me wrong there are also many film schools that do a decent job of teaching at least film theory, even if it still isn’t shown exactly how to add it to your own work. I went San Francisco State University and while attending we had a bit of a rivalry with the Academy of Art film students. We were a bit jealous of all of their fancy, new, high end equipment. Our schools equipment was old, beat up, and less than bountiful. The school was heavy in theory though. I remember leaving hoping I never had to hear about penis envy or the male gaze ever again! After graduation though and seeing the films that came out of the Academy we realized that while they were perfectly polished, they were lacking in depth. Sure they got to use and actual dolly track where we had a beat up wheelchair or skateboard at best, but our films said something. They resonated….well as much as undergrad film school projects can.

Then what education lies outside of film school for those who don’t attend or post film school? Film related non-profits. If you check out what most filmmaker non-profits offer, its usually workshops and panels where successful filmmakers share how they made it. A lot of filmmakers end up thinking that if they just follow those exact steps, they’ll get there too. Unfortunately, most of this advice is useless because the circumstances that led to their success are completely unique and don’t translate to everyone else. As Diane Gaidry who used to run Filmmakers Alliance used to always say they are factories for “navel gazers”. People hoping to achieve some dream of success and fame, but unwilling to do the real work. What is really missing is actual guidance on how to make films that actually resonate. How to do the creative development of the project before you make it. The focus is all on the nuts and bolts of making the thing or the luck of others, not on the work itself.

I recently attended a screening of a prestigious Los Angeles based film lab. I won’t name the lab because I don’t want to bash anyone in particular. I was super excited to go because the program was one I often thought about applying for, though it also seemed extremely hard to get in because it’s super competitive. I had high hopes. When the screening ended I found myself feeling extremely disappointed. I was also a bit confused, how could these films be so lacking in substance? Sure they looked amazingly sleek and polished. They were lit beautifully, most of the acting was pretty good, but with the exception of 1 or 2 of the films I could not understand what they were trying to say. Or better yet if they were trying to say anything at all. They were all coming of age films and sadly I am very burnt out on these types of films, but even still they were missing that more. My disappointment slowly turned to sympathy for these filmmakers. They had attended a program that had let them down. I’m quite sure they might not realize it but they deserved more guidance on the projects. Given the appropriate tools and guidance these films could have been great. Our programs need to do better. They need to do more.

I’m sure there are also many labs out there that are doing a good job or at least trying to. Just from my experience many are not. Which is part of the reason I’m working on creating a new filmmaking non-profit with a mission that flips this typical non-profit education system around, focusing on the craft and helping filmmakers develop their personal voice and help them figure out how to add that more to their work, rather than just chasing success by following someone else’s path. More of that to come in the future.

But for now, we need to do better to be training and fostering artists through what we have. Like here on FilmStack.

Again many are already doing this, like

’s follow up article to closed loop cinema mentioned above, was how to break free of this:Openness to artistic life beyond cinema allows a film to tap into something higher. “We are at the present moment because of all the work that has been done up to now,” says Italian cinematographer Vittorio Storaro. “There is no question that when you make a design, shoot a picture or photograph a movie, it is the representation of all two thousand years of history.” Without that openness, filmmakers start halfway down the tube, drawing only on material that has already been filtered. At best, the end result is a remix; a cover album. One step removed from the Source.

We need more of this. More discussion on how to create cinema that is more, cinema that elevates us. We have a lot of information out there on how to make a film, let’s get more on how to make an ambitiously authored film.

talks about this often in Luz Films. In this post she talks about her creative process:In an effort to make these next two the best they can be, I told her about the two questions I’ve come to ask myself for all my films:

What is the theory the film is testing?

What is the philosophical question driving it?

These questions are a solid starting point no matter what kind of film you’re making. If you’re investing all that time and money into a project, and expecting me to spend my time watching it, the least you can do is have a clear purpose. A reason for creating what you are creating. Every film made is saying something. And no that doesn’t mean that cinema needs to be didactic. You don’t need to beat us over the head with your message or point, but you should have one that comes across through the work. Every film contributes to the ongoing conversation of cinema. So make sure you know what you want to say, and use every filmmaking tool at your disposal to say it as powerfully as possible.

Another great resource for learning how to add more to your cinema is reading some of the insightful film reviews here on Substack. Paying attention to what elements of film they discuss can lead you to realize how you can create more meaning in your work. Here’s a few I thoroughly enjoy and I know there’s many many more out there, wish I could include them all:

, , ,With all of this I am not saying every film needs to be an ‘arthouse’ film. This more is what makes all films transcend. Genre films benefit from adding more as well.

Take a film like Get Out, it’s reach went far beyond that of an ordinary horror film. It did that because it was ambitiously authored by tackling themes of systematic racism and microaggressions. It used the horror genre as a means not just for a quick scare or to just show some gore, but as a means to express the psychological terror of racism. People who normally don’t go see horror films went to see this one. Because it was more than just a horror movie.

Let’s all do our part to add more to cinema, and to share our ideas and practices, and to educate others about how to add more to theirs as well.

The future of cinema needs and deserves more!

After writing this piece, Ted Hope published this post, on How to Win Sundance, which has some great tips on how to do this, so check it out!

Very spot on post. I think the new technical developments wrt cameras on recent films like 28 Years Later, Sinners and F1 were intriguing to audiences and were a great marketing tactic for said films. I think audiences are interested in film as an art form, we just need to give them the language to understand it from that lens, and to know how to talk about it in that way.

Appreciate the mention, thanks!

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com